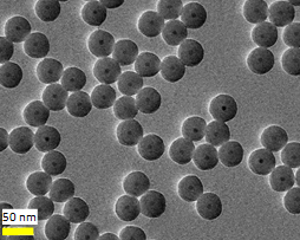

Nanoparticles

Structures confined to nanometer length scales in one or more dimensions can possess strikingly different properties than in bulk. In contrast to bulk materials, low dimensional systems such as nanodots (0D), nanowires (1D), and thin films (2D) have a much larger fraction of their atoms on the surface. As a result, surface physics and interfaces between materials play a much larger role in the overall behavior of these systems. By varying their morphology and composition, their properties can be tailored for applications in pure research or for consumer technology.

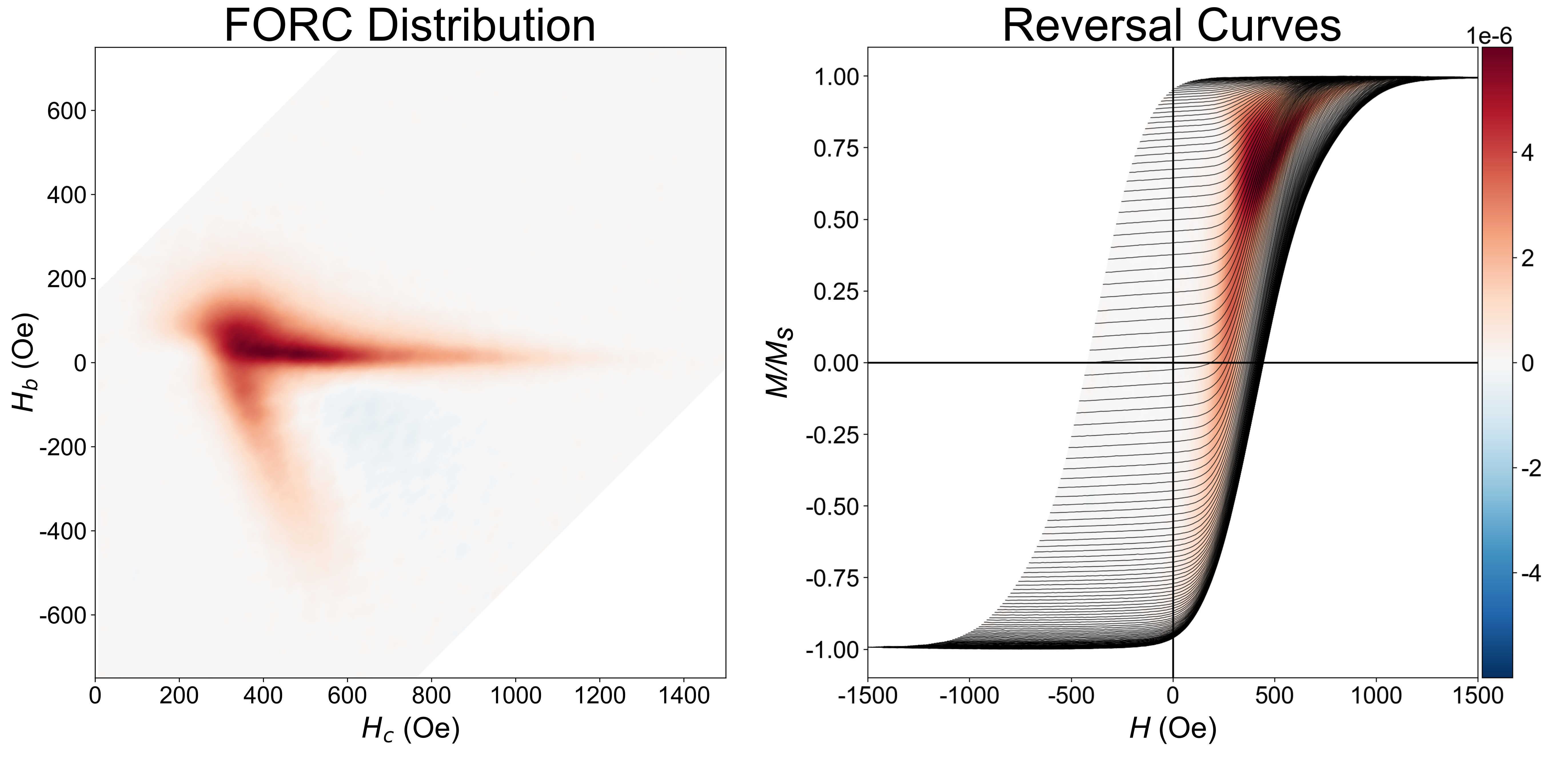

First Order Reversal Curves (FORC)

Magnetic materials are widely used in consumer products, industry, and in research applications. Utilizing these materials in device applications requires an understanding of their behavior from the macroscopic level all the way down to atomic length scales. Alongside micromagnetic simulations (OOMMF, Mumax3), one of the major tools I have used to understand hysteretic behavior is the First Order Reversal Curve (FORC) technique. While simple major loop measurements can yield information about the average magnetization of an ensemble of magnetic moments, FORC analysis allows individual switching events to be probed, revealing microscopic details about iteractions between magnetic moments.

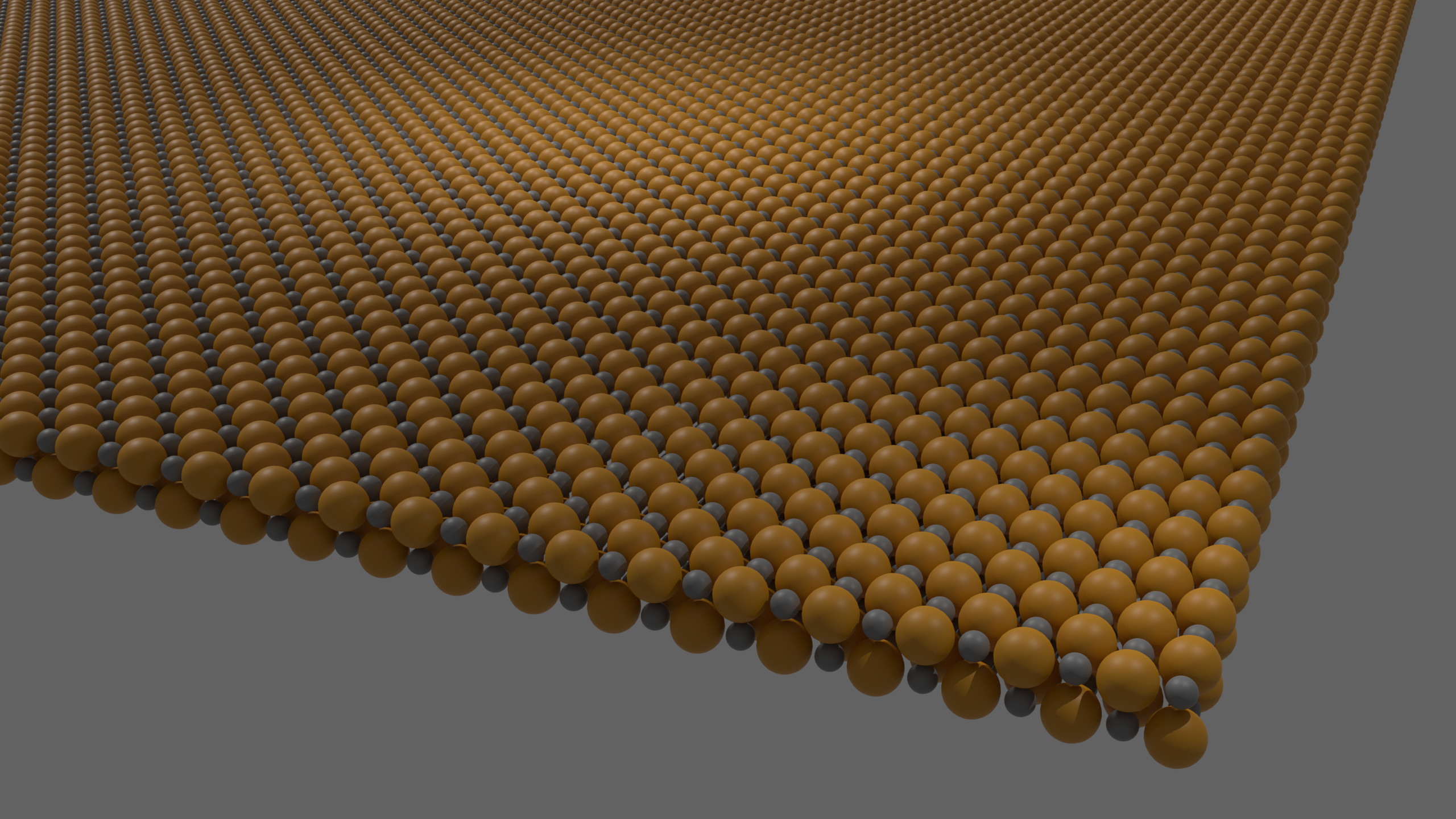

Magnetoionics

Conventional logic and memory technologies which rely on electric currents suffer from Joule heating, limiting their energy efficiency, and are volatile, which requires devices to remain powered in order to maintain their state. The ability to control magnetic materials with electric fields should enable a new generation of nonvolatile memory devices that do not require electric currents, circumventing this limitation. One promising approach towards electric field control of magnetism has focused on solid-state manipulation of ion distributions. My work has focused on the development of methods for chemically-induced and electric-field-induced ionic motion.

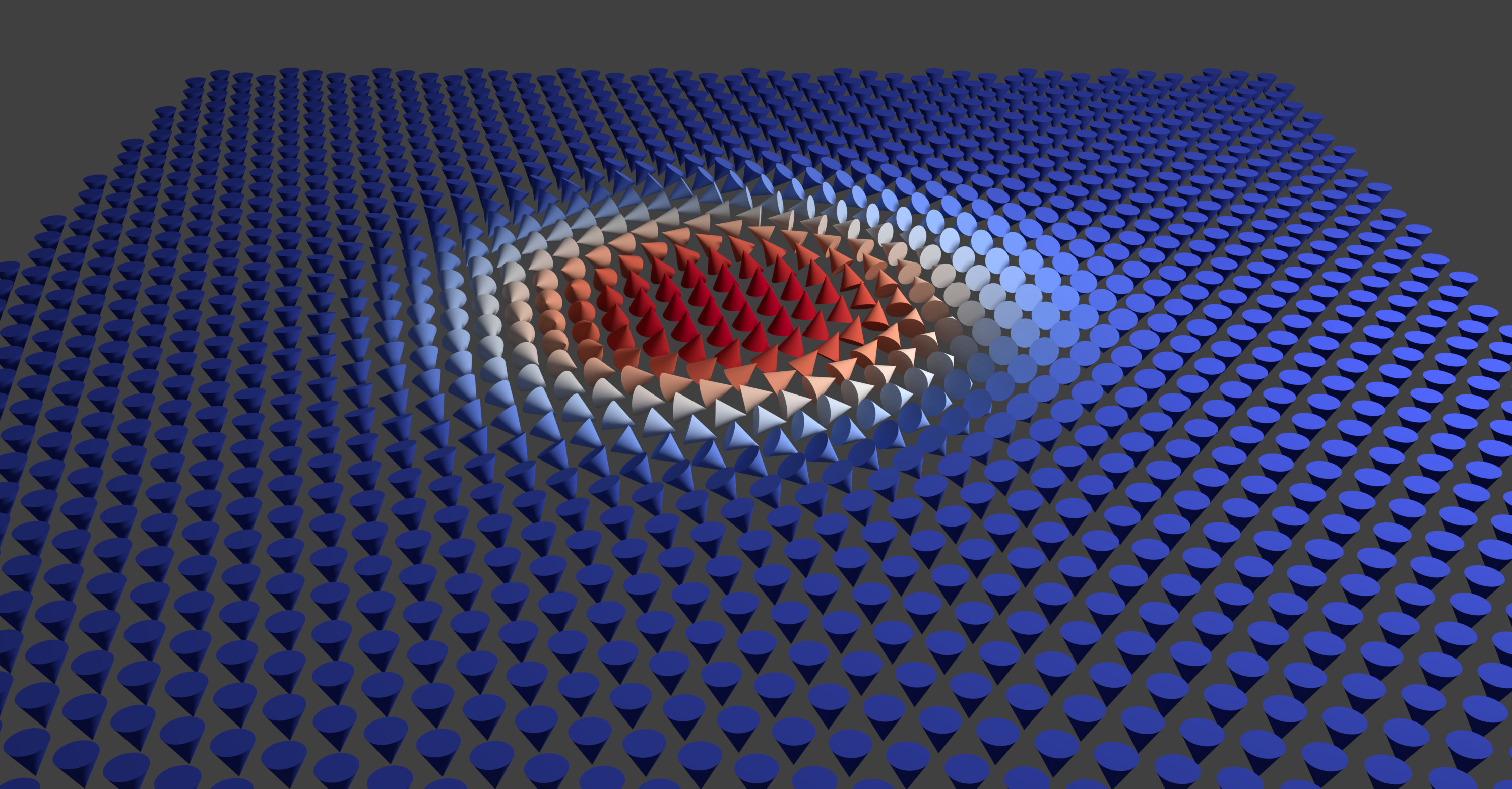

Chiral Magnetism

In certain bulk materials or thin film systems, competing magnetic interactions can lead to winding magnetization textures known as skyrmions. These particle-like textures resemble magnetic vortices, and have extraordinary properties which make them of particular interest both for fundamental physics as well as for nonvolatile, ultra-fast, and low-dissipation storage and logic applications. As part of my doctoral work, I carried out resistivity measurements in search of Hall effect signatures of skyrmions in novel artificial skyrmion lattices.